Early in the morning, in San Francisco, you can see a car slowly driving down from the Ferry Building – stolid survivor of the city’s 1906 and 1908 earthquakes – all the way to Octavia Boulevard, and then back again. It will drive the course four times, each time peppering the city’s exteriors with millions of laser beam lights. City planners in San Francisco have plans to completely revamp the city, but first, they have to take detailed notes of the existing conditions.

Generally, stories of LiDAR – the technological term for those showers of lasers – speak about exactly how researchers use it to map changes in topography after natural disasters or deforestation. Mount a LiDAR system on an airplane, and it should return noticeably comprehensive stories that would certainly have taken weeks and lots of people otherwise.

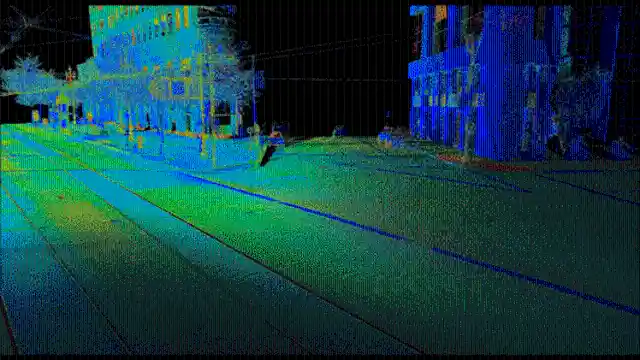

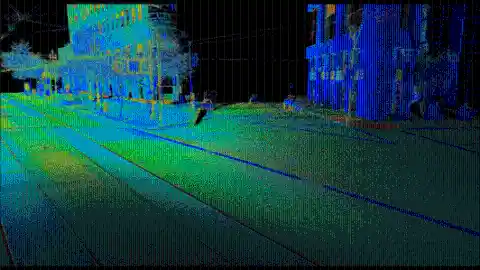

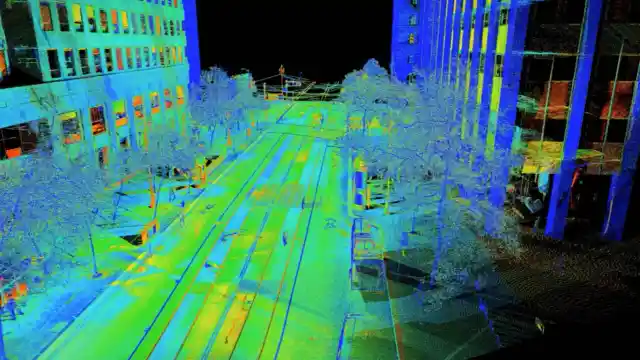

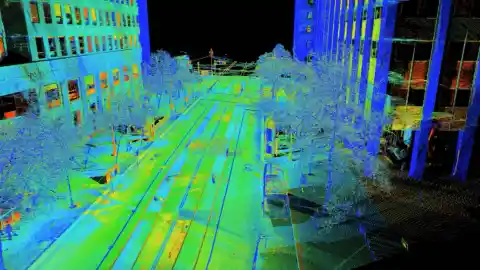

Google’s Streetview cars have had LiDAR scans for some time as well. The business’ initiatives appear concentrated on ground-level information – points like visuals as well as road lines – the type of things primarily of concern for self-driving cars. On the top of a car, LiDAR transforms into an effective device for city planning. In San Francisco’s situation, metropolitan developers want to make Market Street into something better. Treading along a 2.2 mile-long stretch of road at 5 miles an hour, a roof-mounted system called the Riegl VMX-250 will bounce lasers off surface areas and will use the returning beams of light to develop a 3-D map of the vehicle’s surroundings. The slower the vehicle goes, the more opportunities it has to catch every surface area – from the overhanging wires that power the city, to fire hydrants and repainted parking lines.

San Francisco isn’t the only city to use lasers to paint a portrait. Philadelphia has used CityScan to calculate how many billboards there are within the city limits. Though it may seem a little silly, it was incredibly helpful in analyzing advertising placement. Just imagine one person trying to count all of those billboards! The implications of LiDAR are essentially endless. In San Francisco’s case, the objective is to produce an excellent, three-dimensional map of the boulevard – in the nick of time, only to revamp it.